A brief history of the Palestinian issues and events

For this section we have reproduced the political analysis and timelines produced by the Apartheidfeezone.ie.

List of main events in Palestine

The Balfour Declaration (1917)

In November 1917 Britain issued the ‘Balfour Declaration’, in which it promised to use its colonial power to grant the predominately Arab region of the Levant called Palestine to the Zionist Movement – a movement of Jewish nationalist colonial settlers from Europe.

Approximately 7% of the population of Palestine at this time was Jewish – many of them European immigrants – while the rest were indigenous Muslims and Christians.

Britain promised a land that was not theirs to a colonial movement that sought to build an ethno-nationalist state at the expense of the indigenous Arab Palestinians, laying the foundation for what would become the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and the creation of the Apartheid State of Israel.

Zionism was very much an extremist minority position in the wider Jewish world at this time.

The Naqba (1947-1949)

Following the Second World War, the Nazi Holocaust, and the resulting immigration of many thousands of European Jewish refugees into Palestine, the Zionist movement experienced a huge growth in support and confidence. Building on their attacks on British forces stationed in Palestine during and after the war, and following the UN’s undemocratic vote to partition historic Palestine against the wishes of the indigenous people, from 1947 Zionist paramilitary groups began the process of a calculated ethnic cleansing of Arab Palestinians.

By the time the British colonial mandate expired and its forces pulled out on 14th May 1948, some 300,000 Palestinians had already been expelled from their homes. Following the creation of the Apartheid State of Israel and the easy defeat by Zionist forces of an intervention by an outnumbered, outgunned and disunited Arab coalition, the process of ethnic cleansing continued.

By early 1949 at least 750,000 people – two thirds of the indigenous population – had been expelled from their homeland, while thousands had been killed, and thousands more would be killed while attempting to return to their land. Some 500 Palestinian towns and villages were forcibly depopulated and destroyed or left to decay. Those who managed to survive this violence and remain in their homeland lived under strict Israeli military rule – curfews, restriction on movement, martial law, etc – until 1966. Palestinians refer to this period as Al Nakba, Arabic for ‘The Catastrophe’.

By 1950, 78% of historic Palestine was part of the Apartheid State of Israel, with Egypt in control of Gaza, and Jordan in control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Every year Palestinians around the world mark 15th May as ‘Nakba Day’.

The 1967 Occupation

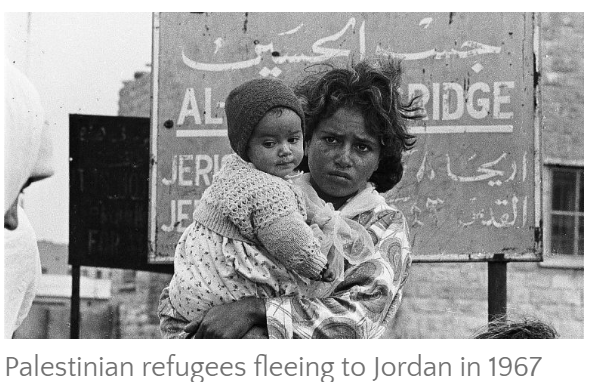

In June 1967, using bogus claims about impending attacks from neighbouring states, Israel launched a colonial war of conquest against Jordan, Egypt and Syria. Beginning with a surprise attack, within just six days the Israeli military had defeated these three Arab armies and occupied the rest of Palestine (Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem), the Egyptian Sinai, and the Syrian Golan Heights.

The Palestinians in these territories then fell under Israeli rule, and have been subjected to a brutal military occupation and apartheid regime ever since. A further 300,000 Palestinians were expelled into the refugee diaspora. Palestinians refer to this period as Al Naksa, Arabic for ‘The Setback’, and it is marked annually on 5th June.

Eventually, in 1982, the Sinai was given back to Egypt as part of a peace deal which saw the Egyptian leadership effectively abandon the Palestinians.

Israeli Settlements

Almost immediately after the end of the 1967 conquest, Israel began the process of colonising the land, building Jewish-only settlements in the occupied territories. All such settlements – whether in occupied Palestine or occupied Syria – are illegal under international law, and are considered war crimes under the Geneva Conventions. This is the position of the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly, the European Union, the governments of Ireland and Britain, the International Court of Justice and all respected human rights organisations.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention states that it is illegal for an occupying power to “deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies”; all such settlements are thus war crimes. UN Security Council Resolutions 446 and 2334 declares settlements have “no legal validity” and are “flagrant violations of international law”.

Today there are more than 200 such illegal settlements in occupied Palestine, with a population of between 600,000 and 800,000. Illegal settlers have also taken over Palestinian farmland, water aquifers, and built illegal and highly pollutive industrial zones near Palestinian towns and villages.

Settlements are one of the most important factors in shaping life for West Bank Palestinians. Their destructive impact on the human rights of Palestinians extends far beyond the thousands of hectares that Israel has stolen to build them.

Land has been expropriated to pave hundreds of kilometers of apartheid settler-only roads; roadblocks, diversions and checkpoints that deny freedom of movement to Palestinians are erected based on the location of settlements; Palestinians have been denied access to much of their farmland; and the Apartheid Wall (begun in 2003, and deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice in 2004) was built in order to leave as many settlements as possible – and lots more Palestinian land – on its western side. Although in theory settlements take up only around 2% of the West Bank, it is estimated that up to 40% of Palestinian land in this area is totally off limits to Palestinians as a result of various factors owing to the presence of the illegal settlements.

The First Intifada years (1987-1993)

In December 1987, after two decades of brutal occupation, oppression and injustice, coupled with the complete failure of the international community to stand up for Palestinian rights and end Israeli apartheid, a spontaneous, widespread and largely unarmed national protest movement began. Palestinians called it the Intifada, which in Arabic literally means ‘shaking off [of oppression]’, but is more accurately translated as ‘uprising’. For six years Palestinians in the occupied territories organised themselves and conducted a hugely effective campaign of civil disobedience; strikes, demonstrations, boycotts, refusal to comply with occupation forces, ‘illegal educational activities’ as Israel closed educational facilities; the flying of ‘illegal’ Palestinian flags and writing of revolutionary graffiti; and confrontations between stone-throwing youths and the heavily armed occupation forces.

Apartheid Israel responded with extreme violence and repression, a policy of “might, power and beatings” imposed by an “iron fist”, in the words of then Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. This entailed the killing and maiming of thousands of protesters, and jailing and torture of political prisoners; horrific images were beamed around the world of soldiers breaking the bones of young Palestinians. In all, around 1,300 Palestinians were killed by occupation forces, roughly 250 of them children. According to Save the Children, almost 30,000 children “required medical treatment for injuries caused by beatings from Israeli occupation forces during the first two years of the Intifada alone”, one third of them under 11 years of age. A further 8,000 children were wounded by live fire during the same period.

Meanwhile, over 175,000 Palestinians were jailed during the Intifada, and in 1990 alone just one Israeli prison held approximately one out of every 50 Palestinian males over the age of 16. During this period Israel had the highest per capita prison population in the world, and the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem estimates that around 85% of prisoners were subjected to torture.

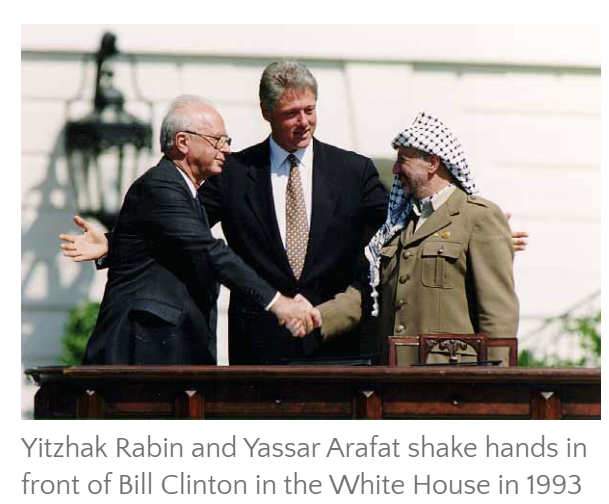

The Oslo ‘Peace Process’ years (1993-2000)

Under international pressure, and Israel’s desire to stave off a ‘South Africa’ moment, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Israeli officials began secret negotiations in Norway that, in 1993, produced the first of the ‘Oslo Accords’. Several more accords and agreements would emerge over the next couple of years. The signing of these accords effectively saw the end of the First Intifada. Although hailed as the ushering in of an era of peace, these agreements in fact failed to adequately address the demands of the Palestinian people who had sacrificed so much for their freedom, not least during the Intifada.

The big issues – real self-determination for the Palestinian people, sovereignty over East Jerusalem, the dismantling of settlements, the final borders of any Palestinian state, and the return of the refugees – did not form part of the agreements; these were instead set to be part of the ‘final status’ negotiations due to take place years down the line. Reparations for decades of colonial brutality inflicted upon the Palestinians were not even raised.

Oslo – The Reality

Instead, the accords saw the PLO renounce armed resistance and recognise Israeli sovereignty over 78% of historic Palestine (i.e., the area that became the Apartheid State of Israel violently established between 1947 and 1949), while Israel recognised the PLO as the representative organisation of the Palestinian people, and agreed to release Palestinian political prisoners. Rather than taking a rights-based approach to national liberation, there was an implied – but far from explicit – commitment to Palestinian statehood in 22% of historic Palestine (in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza), which began with the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) which exercises limited control over some 18% of the occupied Palestinian territories (Area A), and mere municipal administration of another 21% (Area B). The remaining 61% (Area C) remained under full Israel civil and military control – though these designations are practically meaningless as Israeli occupation forces can and do operate wherever they like without regard to who has ostensible control. There were also ‘security’ cooperation agreements under which the PA agreed to police and suppress Palestinian resistance in the areas under its nominal control, and the nascent ‘independent’ Palestinian economy was effectively subsumed into the Israeli one.

During the ‘Olso Period’ (1993-2000), the number of Israeli settlers and settlements dramatically increased, and through outsourcing security and the building of a complex network of checkpoints, roadblocks and settler-only roads that cantonised and cut off Palestinian population centres from each other, restriction of freedom of movement based on an ID-card system, Israel’s occupation was in fact deliberately entrenched. There was never any intention to grant Palestinians their right to self-determination or freedom.

At the time, far-sighted Palestinian intellectual Edward Said wrote that far from being something to celebrate, Oslo was “an instrument of Palestinian surrender, a Palestinian Versailles” which saw “a century of sacrifice, dispossession and heroic struggle finally come to nought” with the PLO’s abandonment of the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people. Israeli historian Avi Shlaim, who at first welcomed the Accords, wrote on their 20th anniversary that Olso “was worse than a charade: it provided Israel with just the cover it was looking for to continue to pursue with impunity its illegal and aggressive colonial project”.

In short, Oslo failed to deliver any real gains for the Palestinian people – some called it the ‘greatest defeat since the Nakba’ – and rather than usher in a ‘peace process’, it began what many call a ‘pacification process’ whereby the official Palestinian political leadership attempted to cede the rights of the Palestinian people in exchange for localised power and privilege. This strategy was to backfire spectacularly.

The Second Intifada years (2000-2008)

IIn September 2000, Palestinians once again spontaneously rose up against the occupation. Understanding that almost a decade of the Oslo process had left them in a worse position than before the First Intifada, a second widespread revolt began following the deliberately provocative visit of far-right Israeli politician and war criminal Ariel Sharon to the Al Aqsa Mosque compound. Becoming known as the Second Intifada, it elicited a much bloodier Israeli response than the first.

During the first weeks of the uprising, Israeli forces shot one million live rounds at unarmed protesters. This use of force expanded to include tanks, helicopter gunships and even F-16 fighter planes, and civilian neighbourhoods and PA institutions were subjected to shelling and aerial bombardment. This was a conscious escalation in the use of force designed to avoid a protracted civil uprising, like the First Intifada – and it was successful. In response, Palestinian frustrations saw a militarisation of aspects of the uprising, which resulted in an escalation of armed attacks and suicide bombings, which had been a tactic of anti-Oslo militant groups in the 1990s. As former Israeli diplomat Shlomo Ben Ami stated, “Israel’s disproportionate response to what had started as a popular uprising with young, unarmed men confronting Israeli soldiers armed with lethal weapons fueled the Intifada beyond control and turned it into an all-out war.”

During this bloody period, almost 5,000 Palestinians, including almost 1,000 children, were killed by Israeli occupation forces or settlers. Just over 1,000 Israelis were killed by Palestinian armed groups, including 120 children. Thousands of Palestinians were wounded and thousands more imprisoned, and more than 3,000 Palestinian homes were illegally destroyed as ‘punitive’ measures, leaving thousands of people homeless.

By 2005 the militarised aspects of the Second Intifada had largely petered out, but the grassroots popular resistance which has always been the backbone of Palestinian struggle continued, as it does to the present day.

Internal Palestinian Conflict

In 2006 an election for the Palestinian Authority was held in the occupied Palestinian territories. The winners were Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement, beating the Fatah party that had held power for the previous decade. Rather than accept the result of these elections (deemed “free and fair” by US and international observers), the international community and Israel sought to isolate and boycott the new government. Internationally, diplomatic ties and financial aid were immediately cut off while Israel, with Egyptian assistance and EU complicity, began its illegal blockade of the Gaza Strip, where Hamas has its main powerbase, and withheld taxes it had collected on behalf of the PA.

To counter this, a Palestinian national unity government was formed – yet this too was unacceptable to the US and Israel. Seeking to overthrow the democratically elected government, the US connived with elements of Fatah to stage a military coup that would oust Hamas. However, details of this so-called ‘Plan B’ leaked, and Hamas instigated a counter coup. The ‘Battle of Gaza’ saw 160 people, mostly partisans for each side, killed and left Hamas in control of Gaza and Fatah in control of the West Bank. These bitter divisions and their enduring wounds were and remain a tragedy for the Palestinian people, severely compromising the unity that is needed to end Israel’s occupation and apartheid.

The Siege of Gaza

After this mini-civil war, Israel tightened its siege of Gaza, the tiny coastal enclave which is home to two million people, the vast majority of them refugee families from 1948, more than half of them minors. This blockade is a form of illegal collective punishment with the aim of undermining the Hamas administration. That this is the goal of the siege has been repeatedly and openly admitted by Israeli officials. This cruel siege has endured and been an aspect of daily Gazan life ever since. With a regime of punishing economic sanctions, a dearth of medical supplies, artificially-imposed food, water and electricity shortages, arbitrary exclusion zones for – and attacks on – farmers and fishers, an unemployment rate of over 50% (the highest in the world), and frequent military incursions, Gaza remains constantly on the brink of a huge man-made humanitarian catastrophe.

Add to this the five large scale assaults on Gaza by the Israel occupation forces since 2006, which cumulatively have left over 4,000 people dead (including some than 1000 children), tens of thousands more wounded, maimed or traumatised, innumerable homes and facilities destroyed, and the civilian infrastructure of Gaza in ruins, and we are left with an incredibly bleak picture.

In 2015 the UN issued a report that stated that Gaza would become “unliveable by 2020”. Two years later, another UN report was issued that reported that “the ‘unliveability’ threshold has already been passed”. At the time of writing Gaza remains under this brutal and illegal siege, teetering on the precipice of catastrophe, awaiting the next Israeli onslaught while the international community continues to sit on its han

The Strangulation of the West Bank

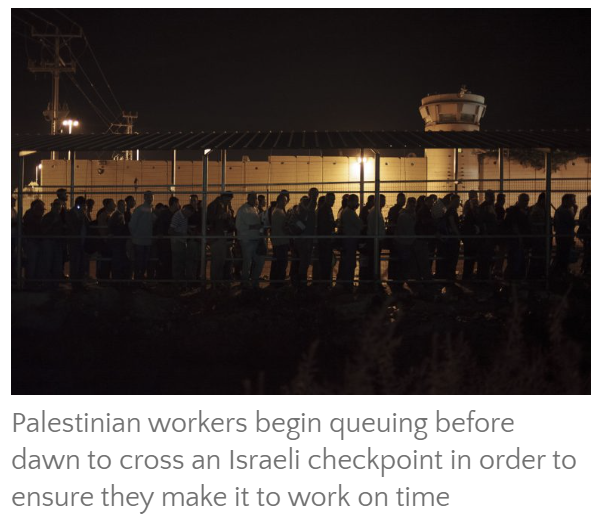

Meanwhile, things are little better in the West Bank where three million Palestinians live. Here, despite the nominal Palestinian Authority control in ‘Area A’, Israeli occupation forces continue to control almost every aspect of Palestinian lives, from the moment they wake to go to work until they retire to bed.

The Apartheid Wall – sometimes called the Separation Barrier – which snakes through the region, the settler-only roads that criss-cross it, and the illegal settlements the wall is there to entrench, combine to choke the life out of the West Bank.

The associated checkpoint regime – there are over 500 checkpoints and roadblocks – impedes, and often denies, freedom of movement and cuts Palestinian population centres off from each other, with people having to queue from very early morning in order to ensure they get to work, school, university or medical appointments on time. 90% of Palestinians are cut off from their economic and social capital of Jerusalem and can only enter with special permits that are extremely difficult to obtain.

Much arable land is either off limits to Palestinian farmers, or has simply been stolen by settlers. What land that is accessible is often the subject of violent attacks by settlers (protected by the occupation forces) with the uprooting of olive trees or the burning of crops. Israel controls all borders and entry points and arbitrarily denies the entry and exit of both people and goods. The unemployment rate is 18%; many of those who are employed work in construction inside Israel, and, in a bitter irony, often in building illegal settlements. Enforced poverty is compelling these workers to build the very settlements that are contributing so much to the collective misery of the Palestinian people.

Killings of Palestinian civilians are frequent. Military raids on villages to drag people, mostly young men and boys, from their beds in the middle of the night are a nightly occurrence; thousands of political prisoners, including hundreds of children, are incarcerated as a result.

Palestinian Citizens of Israel

Often referred to as ‘Israeli Arabs’, though the vast majority do not identify in this way, these are the Palestinians who managed to survive death or expulsion during the Nakba, who became involuntary citizens of the Apartheid State of Israel, and their descendants. Today they number just under 2 million, and make up 20% of the population of the state. According to the US State Department, they face severe “institutional, legal, and societal discrimination”.

For the first eighteen years of Israel’s existence they lived under a system of martial law, similar to that which exists today in the occupied Palestinian territories. In 1966 military rule was finally lifted, but although Israel propagandists claim that Palestinian citizens enjoy the same rights as Jewish-Israelis, they in fact face discrimination in many aspects of life, from land ownership to spousal rights.

Citizenship vs Nationality vs Rights

In Israel, unlike in virtually every other country, there is a distinction between ‘citizenship’ and ‘nationality’. While citizenship is conferred upon all regardless of ethnic origin, these citizens are defined by their ‘nationality’ – Jewish, Arab, Druze, etc. There is no such thing as an Israeli nationality (something that has been tested in court) and this has very real practical effects for non-Jewish citizens. Israel calls itself the ‘nation state of the Jewish people’, and unlike any Western country, it is emphatically not a state of all its citizens, but a state in which non-Jewish citizens are, at best, merely tolerated.

According to Israeli human rights organisation Adalah, there are 65 laws currently in place that discriminate against Palestinian citizens on the basis of their ethnicity, ranging from the ‘legalised’ theft of land, to the denial of residency and citizenship to OPT Palestinian spouses of Palestinians, to the criminalising of boycotts. The most fundamentally discriminatory law of all is Israel’s so-called ‘Law of Return’ whereby anyone with a Jewish grandparent can move to Israel and become a citizen. At the same time, Israel continues to deny Palestinian refugees their legally mandated Right of Return, meaning that someone whose family has never lived in the state can become a citizen, while people living a few hundred kilometres away who were forced from their land within living memory are barred from ever coming home because they are the ‘wrong’ ethnicity.

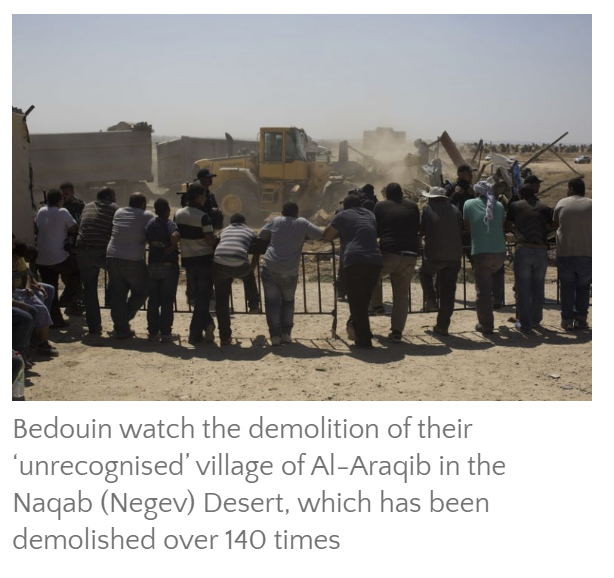

Bedouin watch the demolition of their ‘unrecognised’ village of Al-Araqib in the Naqab (Negev) Desert, which has been demolished over 140 times

Palestinian citizens do not enjoy the same right to access to land as Jewish citizens. The Jewish National Fund (JNF) a racist organisation that controls 13% of the land, will not lease homes to non-Jews. The JNF also has an influential presence in the Israel Land Authority, which controls some 93% of the land in the state. In practice, according to Adalah, around 80% of all land in the state is off limits to Palestinian citizens. Since the creation of Israel, not a single new town for the Arab population has been built while countless Jewish towns have been.

Furthermore, some 400,000 Palestinian citizens are internally displaced people (IDPs) within the state, barred from returning to lands that were stolen when they were declared “present absentees” by the state following the Nakba. Many live in unrecognised villages – often within sight of their original homes which are now occupied by Jewish-Israelis – with no access to public services and the constant threat of home and/or village demolition hanging over them, especially Bedouin people in the Naqab (Negev) Desert.

Discrimination and demographics

Palestinian citizens face economic discrimination, with over 50% of Arab families living below the poverty line, compared with 14% of Jewish families; 66% of Arab children live in poverty. Unemployment rates are higher for Arabs than Jews, and Arabs tend to be employed in lower paid economic sectors; the average monthly wage for an Arab worker is €1,830 compared with €2643 for a Jewish worker, while Arab women on average earn only €1482 per month. Only 10% of civil service employees, and just 2.5% of all high-tech workers, are Arab.

Palestinians citizens of Israel commemorate the Kafr Qasim massacre of 49 civilians by Israeli police

Although constituting 20% of the population, political parties that specifically represent the interests of the Palestinian citizens make up only 10% of seats in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. Only five Arabs have ever served in government (all members of non-Arab majority parties) and no Arab-majority party has ever been invited to form part of an Israeli government. Before almost every general election, legal attempts are made to ban Arab-majority parties and individual Arab politicians from running, and Israeli law prohibits parties that are explicitly anti-Zionist from running in elections. In the realm of justice, only three Arabs have ever served on Israel’s Supreme Court and none of them have been Muslim.

Palestinian citizen are openly referred to as a “demographic threat”; their very existence is seen as a threat to the Apartheid State of Israel, and both political and societal incitement against the Palestinian population is widespread, leading to a climate of fear. In essence, it boils down to this – the very fact that Palestinians procreate in their native land is a viewed as threat to Israel’s colonially enforced demographic balance.

Most recently, Israel passed the so-called ‘Jewish Nation State Law’ which codified much of what was already a de facto racist reality. In declaring that “Israel is the historic homeland of the Jewish people” who “have an exclusive right to national self-determination in it” and enshrining systematic discrimination into its basic laws, Israel has openly declared itself an apartheid state.